26 March 1828: Schubert's only concert

Posted by Richard on UTC 2018-03-22 09:54

Franz Schubert gave only one concert in his life, on Wednesday 26 March 1828, 190 years ago.

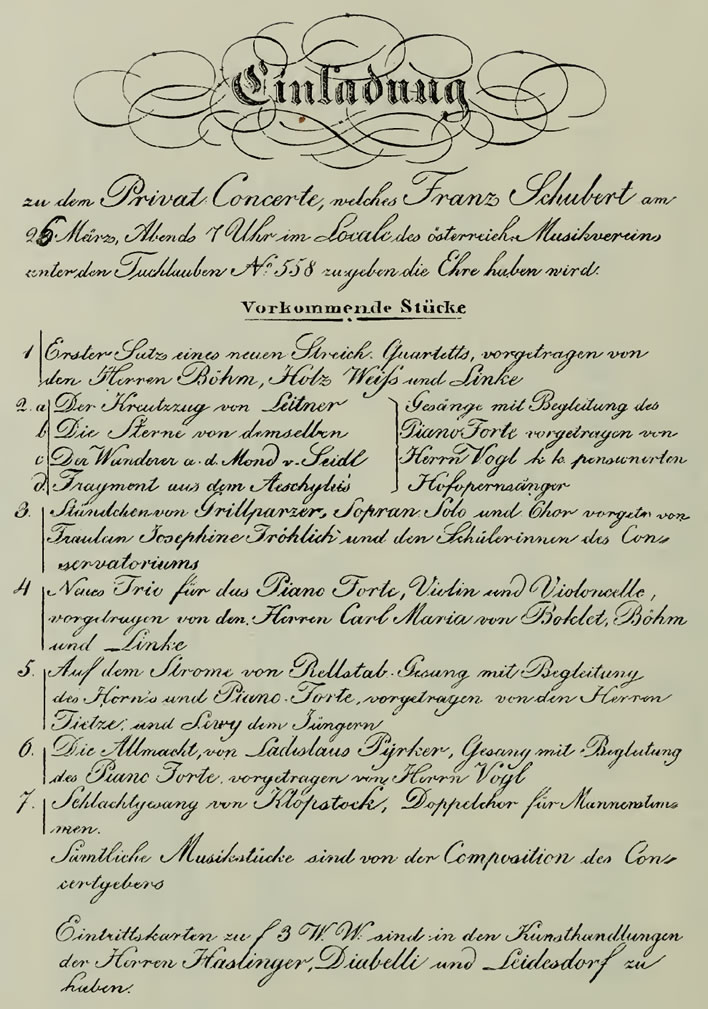

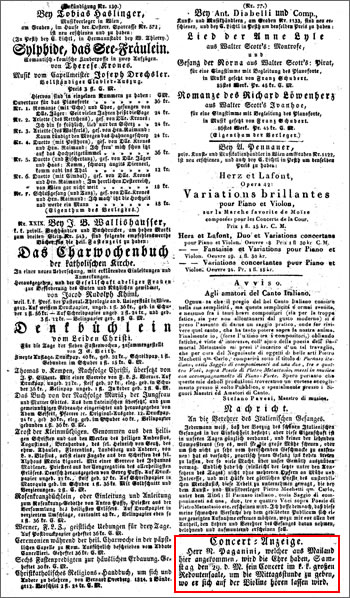

The programme

The programme leaflet for Schubert's one and only concert, 26 March 1828.

Invitation

to the personal concert which Franz Schubert has the honour of giving on 26 March, seven o'clock in the evening on the premises of the Austrian Music Society [sic], unter den Tuchlauben no. 558.

['Privat' should be read as 'personal' not 'private', since the latter would mean that the concert was not open to members of the general public. 'Privat' indicated that the concert was not organized by an official society in Vienna. The date was printed incorrectly as 28 March. The leaflet was printed by Franz von Schober in the 'Lithographic Institute' that he had acquired. The business would fail a few months later.

The correct designation of the locale is Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Wien, 'Society of Friends of Music in Vienna'.]

Pieces to be performed:

- The first movement of a new string quartet, performed by Messrs Böhm, Holz, Weiß and Linke. [This was probably the String Quartet no. 15 in G major, D 887, but may have been the String Quartet no. 14 in D minor, D 810 (the variations on Death and the Maiden, written during the winter of 1825–1826.]

- Songs performed by Herr Vogl (singer of the Imperial Court Opera, retired) accompanied at the piano [by Franz Schubert].

a. Der Kreuzzug by [Karl Gottfried Ritter von] Leitner [D 932, 1827].

b. Die Sterne by the same [D 939, 1828].

c. Der Wanderer a[n] d[em] Mond v[on] [Johann Gabriel] Seidl [D 870, 1826. This piece was not performed. Its place was taken by Fischerweise by Franz Xaver Schlechta von Wschehrd, D 881b, 1826.]

d. Fragment from Aeschylus [Mayrhofer] [D 450, 1816]. -

Ständchen by Franz Grillparzer, soprano solo und choir, performed by Fräulein Josefine Fröhlich and the students of the Conservatory.

[The choice of this piece was particularly appropriate, as the article at the link will explain. The piece was written to mark the birthday of Louise Gosmar (1803-1850), who would marry Leopold von Sonnleithner (1797-1873), Schubert's friend and contemporary, a few months later on 6 May 1828. Sonnleithner was a leading light in the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde, which had been founded by his uncle Joseph Sonnleithner (1766-1835). Leopold and Louise would have enjoyed hearing this piece performed in public. We can assume that Louise was in the choir.] - New trio for Pianoforte, Violin and Violoncelle, performed by Messrs Karl Maria von Bocklet, Böhm and Linke. [Trio in E-flat major, 1827, D 929].

- Auf dem Strome by [Ludwig] Rellstab, song with horn and piano accompaniment performed by Messrs Tietze and [Josef Rudolf] Lewy the Younger [D 943, March 1828, composed specially for the concert].

- Die Allmacht by [Johann] Ladislaus Pyrker, song with pianoforte accompaniment performed by Herr Vogl. [D 852, 1825].

- Schlachtgesang [Schlachtlied] by [Friedrich Gottlieb] Klopstock, double choir for male voices. [D 443, 1816]

All the works performed were composed by the giver of the concert. Tickets at 3 florins W.W. are available from Messrs Haslinger, Diabelli and Leidesdorf.

The Liederfürst, 'Prince of Song', or a proper composer?

The structure of the programme represents a balance between Schubert's instrumental and vocal compositions. Five of the seven items are vocal works. This should not surprise us, since his friends and supporters knew him mainly through his songs – see the obituary at the end of this article for an example of this.

The concert had to meet the expectations of the paying public. The structure of the programme shows without any doubt that Schubert was considerate towards his one and only concert audience, in contrast to, say, Beethoven, whose demands on the attention and musical intelligence of the audiences in his concerts were brutal and pitiless.

Schubert's repeated battles to get his instrumental work performed and printed make a long, sad chapter that we must leave to one side here. In this his first concert he didn't give up on his instrumental work completely, though: the programme strikes a balance between both disciplines.

The very first item – setting the tone of the concert – was a first movement from a string quartet, which, if it is D 887, would have taken about 15 minutes. The other instrumental work was the Trio in E-flat major D 929, which would have taken up about 40 minutes – the longest single piece in the programme. Thus although the instrumental works are numerically under-represented, from the point of view of a member of the audience – the only point of view that matters, ultimately – they would have taken up somewhere between a third and a half of the duration of the concert.

The vocal music chosen consisted of mostly recent works that were settings of quite uncontroversial texts. No censor would worry about this selection, particularly when a piece by that pinnacle of public respectability, Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock, concluded the evening

Unfortunately we have no eye-witness accounts of the concert, so all our human-interest questions must go unanswered. Were his father and step-mother there? We noted recently how much the son wanted to make the father proud of him. And Ignaz, Ferdinand and his other siblings, were they there? Can we imagine the shade of Antonio Salieri, dead nigh on three years, observing his star pupil from a place beyond the candlelight? And what about all the other figures of his biography? Who knows? Better get on with something we do know.

The Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde

At the time of Schubert's concert the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde was renting the building Zum roten Igel, 'The House of the Red Hedgehog', 'conscription number' 558, street address Tuchlauben 12. The society bought the house in 1829 and rebuilt it almost immediately. I know of no illustration of the building that dates from a time before that renovation.

At the time of the concert Schubert was lodging with his friend Franz von Schober in the building next door, Zum blauen Igel, 'The House of the Blue Hedgehog'. Schubert left Schober's apartment in August/September 1828 to move in with his brother Ferdinand (modern address: Kettenbrückengasse 6), which is where he died around two months later.

Publicity

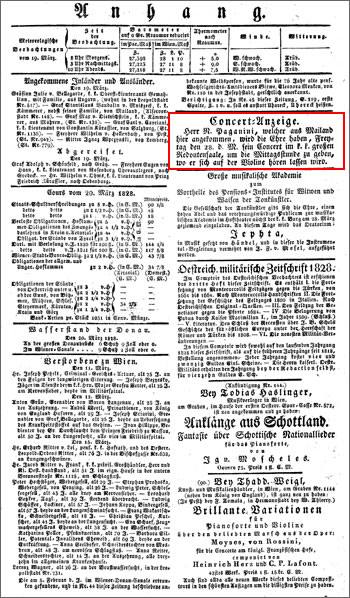

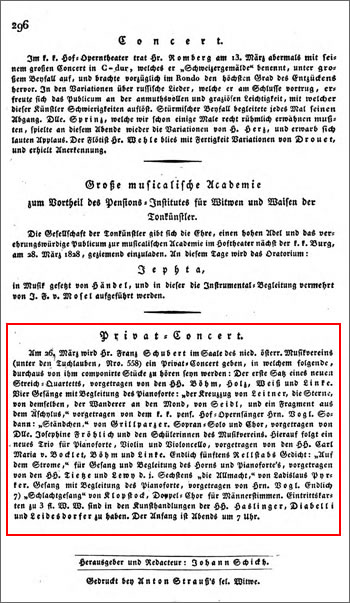

The newspaper announcements of the concert reproduced the contents of the flyer in varying detail. Two examples:

The concert

This concert was an important moment in Schubert's career and life. In numerical terms it was a great success: the concert hall of the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde was full, there was much applause and Schubert even earned some money – 800 florins net. [Dok 504]

To avoid confusion all the monetary amounts in this article are given in Wiener Währung (W.W.). A florin was also in circulation at the time in the form of the Conventionsmünze (C.M.), which was (at the time) 2.5 times more valuable. The term 'Florin' was used in both systems, the term 'Gülden' mainly for Conventionsmünzen.

What was a florin W.W. worth in modern money? There is no easy way to answer this given how different from that time modern life is. We can really only look at the florin's buying power at the time. For example, the reader may remember Schubert's joking reference to what Anselm Hüttenbrenner was paying for his 'hutch': '30 florins Wiener Währung per month'. Schubert's 800 florins could have kept Anselm in his hutch for two years.

It is not completely clear who or what prompted Schubert to hold the first concert in his life, but his friend Leopold von Sonnleithner suggested in his memoir of Schubert that the composer's prodigious output had so overwhelmed the Viennese music publishers by that time that he was having difficulty getting any more work of his published. No publication, no income – so a solution had to be found. That solution was the concert. [Erinn 133]

The concert marked Schubert's breakaway from the Schubertiade as the principal performing stage for his talents. The Schubertiaden had started on Franz von Schober's suggestion in January 1821. They brought the young, unknown Schubert a wider public, a reputation and recognition within the 'Circles of Friends', a performance opportunity and – last but not least – free wine and food.

On this website we take the view that, despite all these positives, the evenings for the Circles of Friends and their friends were ultimately a form of exploitation. Schubert was never paid for his labours – a glass or two of punch and a few bites of game pie doesn't do it.

The friends who benefitted from the Schubertiaden– as entertainment, an opportunity for social dallience or whatever – never seem to have been aware of this exploitative aspect, or if they were, none of them – at least to my knowledge – recorded any hint of this awareness.

Except, that is, for a latecomer to the Schubert circles, Eduard von Bauernfeld (1802-1890), who later alluded politely, humorously but unmistakably to the exploitation of his friend Schubert at these events. He could not rage against such exploitation, he had himself to live and work with these people in the fundamentally exploitative framework of a feudal society.

The three creative musketeers

Schubert first met Bauernfeld in 1822, but they became close friends only after March 1825. It is important to know this, because Bauernfeld was not one of the intimates of Schubert's youth and early adulthood.

Schubert was 28 and Bauernfeld 23 when they became close – another important fact. As Goethe pointed out in relation to his friendship with the older man Herder, a few years difference in age are important when you are young. Bauernfeld was the junior partner by five years. The artist Moritz von Schwind (1804-1871), who was the third of the trio of these late friends, was even younger – seven years. Schubert was, at last, the senior partner in a friendship. The three made up a fellowship of creative artists attempting to scratch a living in imperial Vienna.

Most of Schubert's other friends were independently wealthy to some degree (Schober, the Hüttenbrenners etc.) or had careers in the imperial bureaucracy which brought them security and a steady income (Mayrhofer, the Spauns, Sonnleithner etc.). In their student days some of these people may have had to scrape along for a time, but that was only a passing phase.

In Schubert's youth the closest person to him was probably Johann Senn, an ascetic character of fiery principles who scorned money and the feudal system – but he was brutally taken away from Schubert in 1820. As friends, Bauernfeld and Schwind might relate to Schubert in much the same way as Senn did. Who knows?

Bauernfeld was a writer and dramatist. As a result his entertaining anecdotes are not totally to be trusted: with professional authors the line between 'Invention and Truth' (Goethe™) is lightheartedly crossed in the cause of a well-told anecdote. With that caveat in mind, though, Bauernfeld's memoirs offer us an insight into Schubert's economic situation as a creative artist, an insight that is not invention.

As we have already suggested, Bauernfeld, trying to make a career as a writer in Vienna, was in the same boat as Schubert, who was trying to make a career as a composer there, and in the same boat as Schwind, who was trying to make a career as an artist there. Bauernfeld writes with feeling about the 'ebb and flow' of the creative artist's struggle for income that affected all three of them. He saw that the Schubertiaden fed and watered Schubert (and him and Schwind, to some extent), but also saw how fundamentally exploitative these events were:

Then Schubert evenings came round again, so-called 'Schubertiaden' with cheerful and young companions, where the wine flowed in rivers, the excellent Vogl did an excellent job of performing all the wonderful songs and poor Franz Schubert had to accompany him, until the short fat fingers could barely function any longer.

It was even worse for Schubert at our house parties – we only got 'sausage balls' to eat in those simple times – although there was at least no shortage of charming women and girls. On these occasions our 'Bertl' – as he was flatteringly known by then – had to play his newest waltzes again and again until an endless cotillion had developed, so that the little, corpulent man, sweat rolling off him, only found the contentment of a modest supper.

It is no surprise, then, that he broke away from time to time and even some Schubertiaden had to take place without Schubert if he was not feeling sociable or one or the other of the guests was not to his taste. It was not seldom that he let an invited group wait for him while he was sitting contentedly with a glass of wine along with a half-dozen teaching assistants, his former colleagues, in a quiet pub somewhere. When we remonstrated with him the following day he would say with a chuckle: 'I wasn't in the mood!'

[Erinn 262]

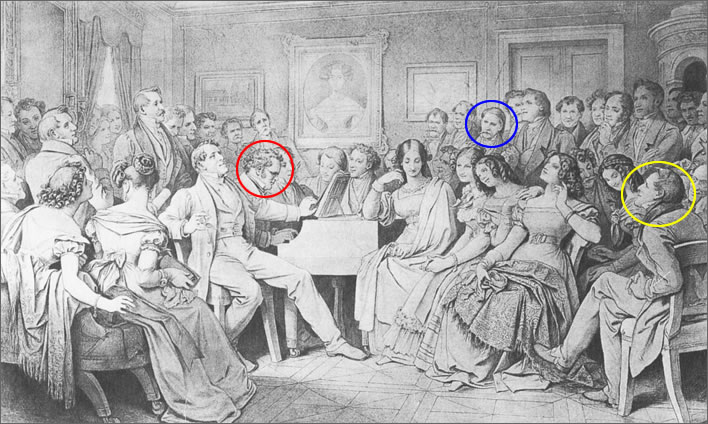

The last ever Schubertiade was held at Joseph von Spaun's house on Monday 28 January 1828. The event is thought to be the model for Moritz von Schwind's famous representation of A Schubertiade at Joseph von Spaun's house. The Schubertiade season.

Moritz von Schwind's homage to a Schubertiade. This was drawn in 1868, 40 years after Schubert had died, and is therefore not really a portrait of any particular event but more of a group portrait of the people in Schubert's life.

In the context of the present article we note the locations of the 'three musketeers' that make such a fine compositional triangle: Schubert (red), Schwind (blue) and Bauernfeld (yellow) – nothing a good artist does is ever an accident. Schubert is in the centre, of course. Bauernfeld – Schwind's lifelong friend – is at the edge, but the second largest figure in the entire scene.

This illustration shows the acceptable face of a Schubertiade. At the start of the evening Schubert and Vogl would do their elevating stuff before the elevated guests, but when the elevating part had finished there would be gossip, dancing, punch and food just like any other Viennese evening salon. Other pianists might contribute to the music, but it was Schubert who carried the main burden of playing for the dancing and for his supper.

Ill-luck

The concert that was held three months after that last Schubertiade, on 26 March, thus promised to be a great turning point in Schubert's career. Unfortunately, the great benefits of the concert were negated by two great pieces of ill-fortune: Paganini and the Grim Reaper.

The Paganini blight

For his many admirers, Schubert's concert stood out from the mass and was well attended, but the reviews in the Austrian press were drowned under the tsunami of Paganini's concert series.

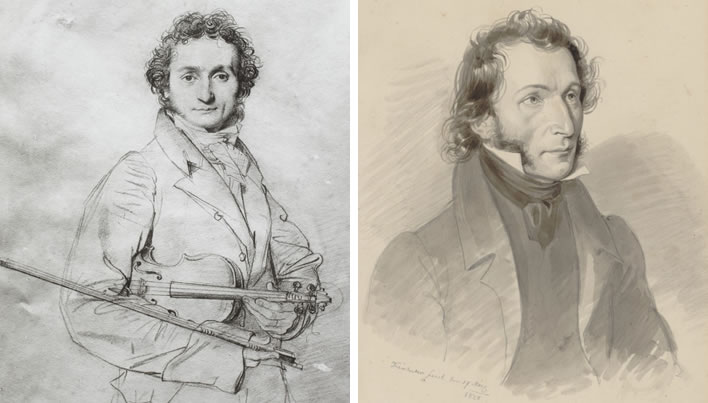

By the time he started his series of concerts in Vienna Niccolò Paganini (1782-1840) was not just a virtuoso violinist but already a legend in his time. His playing style was spectacular, 'demonic' some thought.

The superstar arrived in Vienna on 16 March 1828 and gave his first Viennese concert on 29 March in the Großer Redoutensaal. Otto Deutsch tells us that the attendance for the first concert was only moderate, but after that the series took off.

Niccolò Paganini.

Left: A sensitive portrait from 1819 by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780-1867). Image: A reproduction in the Bibliothèque nationale de France of the original in the Louvre.

Right: Portrait of Paganini dated 17 March 1828 (i.e. shortly after his arrival in Vienna a few days before his first concert there) by Josef Kriehuber (1800-1876). Image: Bibliothèque nationale de France.

For the next few months Vienna was beset by a Paganini craze. The press was full of announcements of concerts, reviews of concerts; there was Paganini fashion and Paganini cuisine; every conceivable household item was available with his portrait; writers, poets, painters and musicians strove to get an allusion to Paganini in their works. Emperor Franz decorated him as a 'Kaiserlicher Kammervirtuose', 'Imperial Chamber Virtuoso'.

The announcement of Paganini's first concert, on Friday 28 March, in the Wiener Zeitung of Friday 21 March 1828. Paganini's concerts in the Redoutensaal were held at noon. [Click to open a larger version in a new tab.]

Hasty planning. The concert planned for 28 March had to be postponed to the following day, Saturday 29 March. Here is the announcement with the new date in the Wiener Zeitung of Friday 28 March 1828. It may well be that the modest attendance at the first concert was the result of confusion over dates resulting from the postponement at such short notice. [Click to open a larger version in a new tab.]

A breathless review of Paganini's first concert on 29 March taking up almost a full page in the Wiener Theaterzeitung, Saturday 5 April 1828. The review confirms without a doubt that Paganini's first concert took place at midday on Saturday 29 March.

Apart from that it consists of much flatulent philosophising and general windbaggery, the likes of which no unpaid translator should be expected to render into English. [Click to open a larger version in a new tab.]

Paganini extended his stay in Vienna several times, staying four months in the end and giving, in all, fourteen concerts. He left Vienna in August of 1828 to take a spa treatment in Karlsbad. He would go on to conquer many other countries on his European tour.

Paganini's mindless virtuosity is not to my taste. There is a megadose of it on Youtube in Itzhak Perlman's stunning recording of Paganini's 24 Caprices. One hour sixteen minutes – three minutes of it is my limit. Those who want more out of music than boastful virtuosity should listen to Schubert's String Quartet no. 15 D 887, the first movement of which he used to open his concert.

Poor old Schubert, who did far more for Austrian music than Paganini, never received any decoration – as far as we know was never noticed by the Emperor or any of those in his vicinity (unlike Beethoven).

Otto Deutsch reproduces the two lukewarm and quite snide sentences about Schubert's concert that the Allgemeinen musikalischen Zeitung in Berlin managed to put into print more than three months after the performance, noting that they followed several columns of coverage of Paganini's first concert:

Herr Franz Schubert, who in a personal concert brought only his own work, mostly songs, to our ears; a genre in which he usually produces successfully. His numerous assembled friends and protectors did not fail to produce frenzied applause for every piece, some with encores.

Dok 505: 'Aus der Berliner „Allgemeinen musikalischen Zeitung“ vom 2. Juli 1828 (Korrespondenz aus Wien)'

In the principal Viennese papers we search and search but find nothing, only Paganini.

Schubert seems to have had little luck in his life, his loves or his career. Even his attempts at operatic works were submerged under another tsunami that went by the name of Gioachino Rossini (1792-1868), which struck Vienna in 1816 and kept the city under the waters of Italian opera until well after Schubert's death. Not only the quantity of performances of Rossini's works themselves was overwhelming, but also the demand for Rossini-style compositions – yet another competitor for the production capacity of the Viennese music publishers.

Money talks

As we have said, Schubert earned 800 florins net from his concert. The ticket price was three florins In contrast, it cost five florins to get into the stalls in Paganini's concert in the Großer Redoutensaal and ten florins in the gallery. Deutsch tells us that the Viennese cab drivers took to calling the five-florin note a 'Paganinerl'. [Dok 505]

Deutsch also tells us that each of Paganini's concerts in the Großer Redoutensaal brought in on average 6,250 florins, altogether about 50,000 florins. Including the concerts in the Hoftheater this would make 75,000 florins altogether for Paganini's six months in Vienna. [Dok 505]

Compare Paganini's income for these six months with the amount Schubert earned in his entire lifetime. Deutsch worked it out with some guesswork and came up with the figure of 22,277 florins. [Dok 592f 8,911 fl. CM.]

Bauernfeld tells a nice anecdote that illuminates the poverty of the three creative friends in the context of his attendance with Schubert at one of Paganini's concerts. Schubert's interest in Paganini was not simply that of a composer and fellow musician, but also that of a violinist. The violin was the first instrument Schubert was taught to play (as an eight year-old, initially by his father). A basic competence in the instrument was an entry requirement for the Stadtkonvikt, where he also received violin lessons and played the instrument in the school orchestra.

Whoever of the three of us [Bauernfeld, Schwind, Schubert] had money, paid for one or the other two. From time to time it happened that two of us had no money and the third – no money at all!

Of course Schubert would play the role of Croesus among the three of us when he swam in silver from time to time, when he had sold a couple of songs or a complete cycle, such as the 'Songs from Walter Scott', for which Artaria or Diabelli paid him 500 florins – a payment with which he was fully content and with which he intended to put his finances into order, although, as always, the task got no further than the intention.

The first period thereafter was lived in careless consumption, money gifted left and right–then finally, once again, Scrooge took over the kitchen! In short, ebb and flood alternated.

It was a flood phase that I have to thank for the fact that I got to hear Paganini. The five florins demanded by this concert pirate were beyond me; that Schubert had to hear him was obvious, but he did not want to listen to him again without me; he was seriously angry when I refused to accept the ticket from him. 'Stupid thing' he shouted – 'I've heard him once already and was annoyed that you were not there too! I tell you, a chap like that will not be seen again! And I have money like chopped straw – so come! – With that he dragged me along.

Who could have resisted his pleas to go? We listened to the devilish-heavenly violinist, over whose fantasies Heine had fantasised so beautifully, and were no less enraptured by his wonderful Adagio than amazed at his other devilish skills, as well as amused at the incredible bows of the demonic figure, who seemed like a skinny black puppet jerked around by strings. After the concert I was as usual entertained in the pub and drank one bottle more than usual at the expense of the enthusiasm.

[Erinn 261]

An interesting aspect of Bauernfeld's description is that he explicitly mentions the proceeds from the sale of the 'Songs from Walter Scott'. The music publisher Matthias Artaria published these in 1826. Scott's works were experiencing a boom in Europe at the time and Artaria paid Schubert 500 florins, which accords with the amount that Bauernfeld mentions. [Erinn 279]

However, Bauernfeld doesn't say that this was the particular 'flood' that paid for his ticket to Paganini's concert and the boozy session afterwards. He writes that is was 'such a flood'. In all probability the flood that took Bauernfeld and Schubert to hear Paganini came from Schubert's income from his concert on 26 March. At 800 florins it was an even greater flood than he received from his settings of the Scott poems. It seems likely that Schubert went to Paganini's first concert on 29 March and then went again with Bauernfeld on 9 May.

Death

Sooner or later the Grim Reaper appears and sweeps his scythe without care through petty human affairs. In Franz Schubert's case it was sooner rather than later.

He was struck down with the typhus that would kill him sometime around 11 November 1828. He died on 19 November, a couple of months short of his 32nd birthday. He had had only around seven months to capitalise on his first concert before he was cut down in his prime – a cliché, but in this case quite appropriate. Seven months were not enough. In the couple of years before his death he had produced some of his greatest work, but he ran out of time.

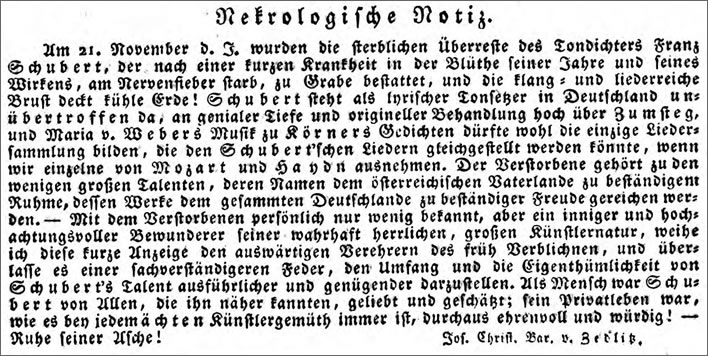

Schubert died on 19 November 1828. His funeral took place on 21 November. Here is the obituary placed in the Wiener Zeitschrift by Josef Christian Baron von Zedlitz, the first obituary Schubert received. Zedlitz was no intimate of Schubert's as he tells us himself: 'With the deceased personally I was little acquainted', but his tribute is nevertheless warm and fitting:

[…] Schubert stands as a lyrical composer unexcelled in Germany, in the genius of his depth and his original treatments high above Zumsteg, and Maria von Weber's music for Körner's poems is probably the only song collection which can be compared with Schubert's songs, leaving aside individual pieces from Mozart and Haydn. The deceased belongs to those few great talents, whose names are credits to the Austrian Fatherland, and whose works give the whole of Germany lasting pleasure.

It is an example of something which in Schubert's life had been so rare: broad public recognition. Unfortunately, the obituary continued the tradition of (de)classifying Schubert as principally a song composer. Franz Schubert was now beyond caring, though. [Click to open a larger version in a new tab.]

Sources

All sources are in German, unless otherwise noted. All translations ©FoS.

The reproductions of newspapers are from the excellent ANNO website of the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek.

| Dok | Deutsch, Otto Erich, ed. Schubert: Die Dokumente Seines Lebens. Erw. Nachdruck der 2. Aufl. Wiesbaden: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1996. [DE] |

| Erinn | —, ed. Schubert: Die Erinnerungen Seiner Freunde. Wiesbaden: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1997. [DE] |

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!